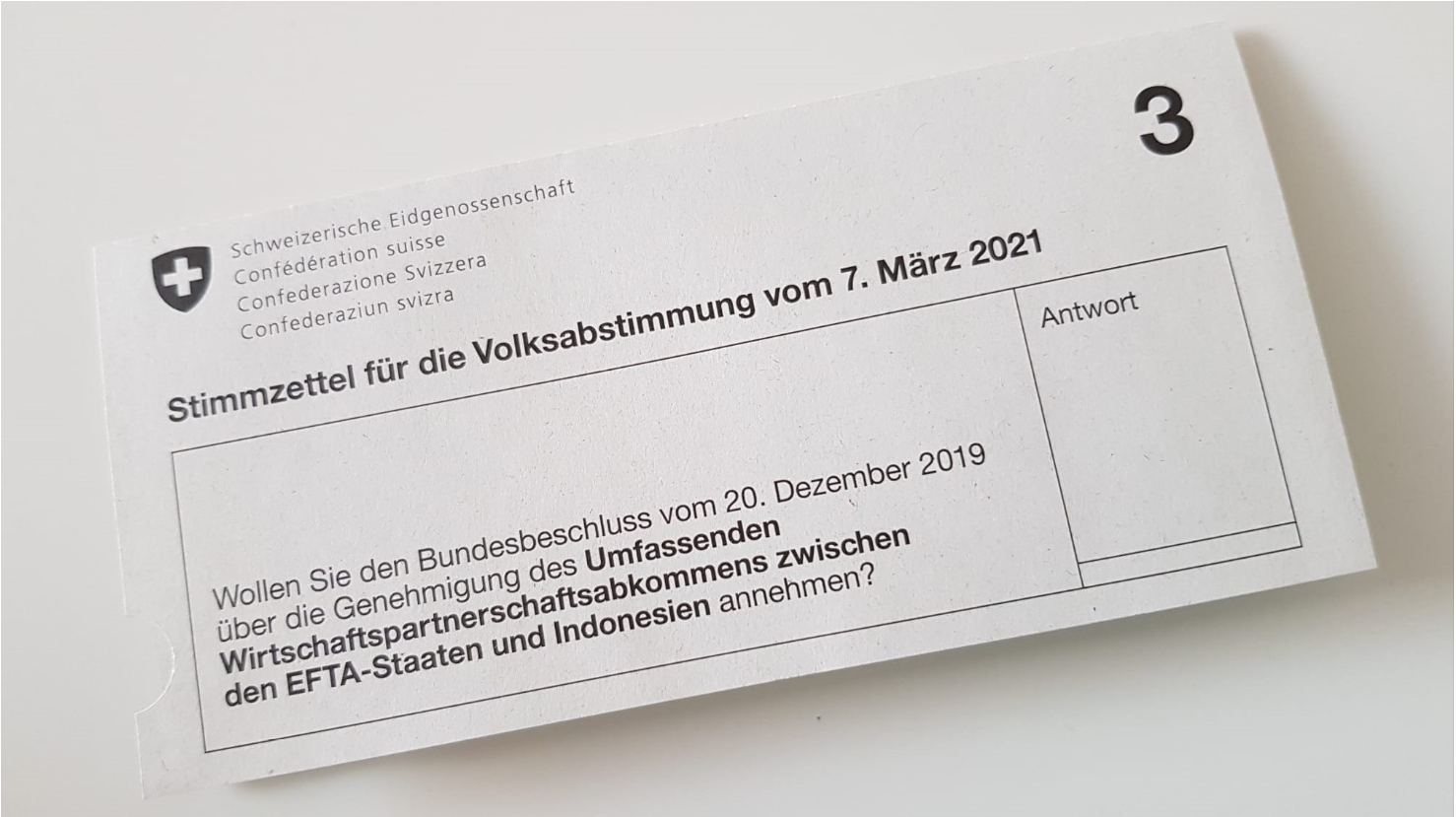

The oil palm issue in the vote of the Free Trade Agreement between EFTA countries and Indonesia (Switzerland, 7 March 2021)

Télécharger la version française.

The OPAL* project has been working for the last six years with oil palm smallholders, companies, conservation organisations, district officials, and government ministers of oil palm growing countries. In view of the upcoming vote in Switzerland, we would like to present below our point of view with regards to the production and trade of oil palm. We do not give any voting recommendation, nor do we position ourselves with respect to trade agreements in general.

1) Impact of other oils. Palm oil is one of several vegetable oil commodities that have had substantial negative environmental and social impacts (Palmöl ist Fluch und Segen zugleich, Tages-Anzeiger (Feb. 2021)). We advocate efforts to improve the sustainability of palm oil production. We emphasise, however, that it is inappropriate to focus only on palm oil without also considering the environmental and social impacts of alternative vegetable oils. Restricting palm oil imports will likely require substitution from other vegetable oil commodities. Some of these commodities also have substantial negative environmental and social impacts that are at least comparable to palm oil (see article from 2018: Substitutes may make matters worse (ETH Blog) / Die Alternativen zu Palmöl sind noch schlimmer (Tagesanzeiger)). Restricting palm oil imports might therefore simply shift environmental and social impacts to other localities if palm oil is substituted by rapeseed, sunflower, soy, coconut, or other such crops. We argue it is important to do a full environmental and social impact that takes account of product substitution prior to any decision.

2) Switzerland has decreased its total palm oil imports in the last 10 years, and Indonesian palm oil represent less than 1% of current imports. Sustainability and reputational risks have made the Swiss industry to import palm oil from less controversial sources. Whether the trade agreement between EFTA countries and Indonesia is approved or not, Indonesian palm oil will still be able to be imported. Given the above reasons, it’s very uncertain to predict whether the approval or rejection of the agreement will increase or decrease further palm oil imports from Indonesia.

3) Switzerland is a net importer of vegetable oil, including not only palm oil but also rapeseed oil and sunflower oil. The country does not have enough land or capacity to produce the vegetable oil that it needs both for its internal consumption but also for its exports (e.g. of emblematic products like chocolate).

4) Less leverage . Disengaging in the oil palm debate with producing countries such as Indonesia will lead to a loss of Swiss leverage and influence on the sustainability of the sector. While we recognise that palm oil production continues to be environmentally and socially damaging in many contexts, we also highlight the many improvements in production practices, supply chain processes, and certification in the palm oil industry. As a result, palm oil cultivation can have tangible social and environmental benefits in in many other contexts. These shifts have resulted, in part, through the scientific, industry and political dialogues where Switzerland and major palm oil producing countries participate.

5) Improving and implementing sustainability standards is an ongoing process. Favouring imports of certified palm oil only will send a strong message to producer countries. Many producer countries and companies are working towards improving standards, improving uptake of such standards, and enhancing enforcement and transparency, but this remains a development process. Currently, it remains challenging to prove that all imported palm oil is entirely sourced from certified sustainable production systems. A more constructive approach might be to recognise current realities, and continue to work constructively with producer countries to improve the social and environmental sustainability of commodities such as palm oil. Overly restrictive policies/measures might otherwise undermine existing and ongoing efforts to embed sustainability criteria across palm oil production systems in Indonesia and elsewhere.

6) Shift to less sustainability-conscious markets. A barrier on palm oil imports into Switzerland will likely encourage producers to seek markets elsewhere, and particularly in countries that are less focused in addressing the social and environmental challenges of palm oil cultivation. Once such markets are developed and established, it will be far more difficult to improve management practices in producer countries and companies.

7) Our activities in Indonesia. The OPAL project has been working with stakeholders in Indonesia at local and district scale to guide and foster increased consideration and implementation of sustainability concepts at all levels and among various actors. While there is still much to do, the OPAL project has contributed to improvements in sustainability systems and criteria (i.e. independent certification and monitoring), smallholder’ integration into sustainable supply chains, and policy processes that seek to enhance management of landscapes and environment. Engagement of Indonesian governmental and private sectors with NGOs and academia has been an important part of this process. Restricting palm oil imports from Indonesia could undermine and even reverse such successes, built through collaborative Swiss-Indonesian ventures, which could ultimately slow the drive to sustainability.

We recognise that there are strong and passionate arguments on both sides of the palm oil issue, and we do not claim that there is a right or wrong position in this highly complex issue. In recent years there have been improvements towards sustainable palm oil, but there is still much more to do. We believe that continued constructive engagement with producer countries will be more effective in reaching sustainability goals. The OPAL position is to maintain such constructive dialogue through collaboration.

*The Oil Palm Adaptive Landscapes Project (OPAL) is an SNSF/SDC-funded project led by the Professorship of Ecosystem Management and the Forest Management and Development group at ETH Zurich. The project has been working in producer countries in Asia (Indonesia), Latin America (Colombia) and Africa (Cameroon). The project includes as partners international institutions (CIFOR, CIRAD and WWF), universities (Pontifical Javeriana University, IPB University, and EPFL Lausanne), oil palm advisory service (NES Naturaleza), and several local grower associations. The project has sought to understand the socioecological factors shaping transformations in oil palm landscapes, and to identify and promote levers of change to steer palm oil production systems and supply chains towards sustainability.

For further information about the OPAL project, and oil palm in Indonesia, Cameroon, and Colombia, please contact Ariane Hangartner (ariane.hangartner@usys.ethz.ch) or Jaboury Ghazoul (Jaboury.ghazoul@env.ethz.ch).

The text is also available as PDF in English, French, and German.

Location

Oil Palm Adaptive Landscapes (OPAL)

c/o Prof. Jaboury Ghazoul

Chair of Ecosystem Management

Department of Environmental System Sciences

ETH Zurich

Universitätstrasse 16

8092 Zürich

Switzerland